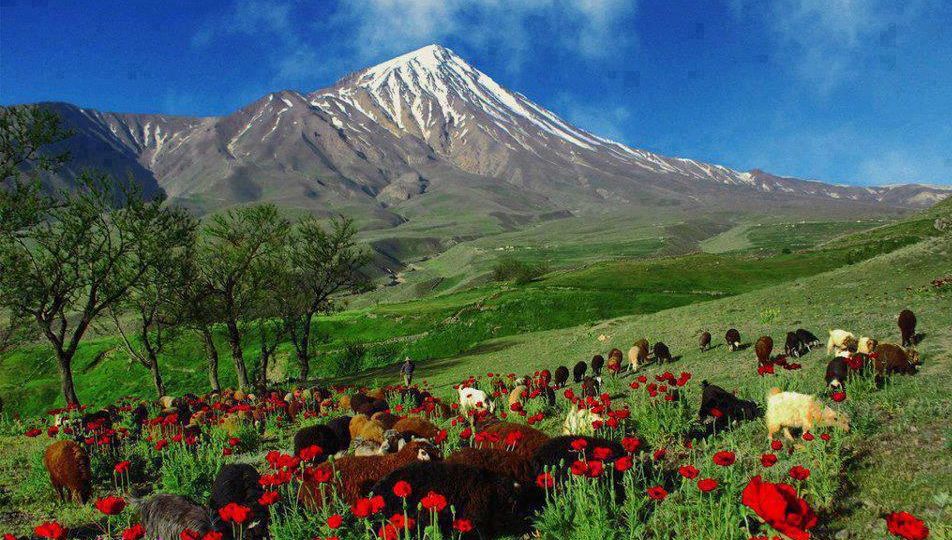

When you think of the Middle East, you might imagine palm trees, camels, and deserts. This is not the Middle East of the Kurds. Kurdish country is a land of high mountains and great rivers.

The Kurds live in a region called Kurdistan, which appeared on maps prior to World War I. Much of the region consists of areas in the central and northern Zagros Mountains, the eastern two-thirds of the Taurus and Pontus mountains, and the northern half of the Amanus Mountains. The 230,000 square miles that make up Kurdistan are stretched across the countries of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Kurds are the fourth largest ethnic group in the Middle East, but they have no modern nation of their

The Kurds live in a region called Kurdistan, which appeared on maps prior to World War I. Much of the region consists of areas in the central and northern Zagros Mountains, the eastern two-thirds of the Taurus and Pontus mountains, and the northern half of the Amanus Mountains. The 230,000 square miles that make up Kurdistan are stretched across the countries of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Kurds are the fourth largest ethnic group in the Middle East, but they have no modern nation of their

own.

Throughout this century and earlier, Kurds have fought to regain control over their ancestral

territories. They want to be a respected nation among nations. The Kurdish independence fighters are

called Peshmerga (those who face death). As in every conflict the world over, the Kurdish civilians suffer most from the Kurdish struggle for self-determination. Until recently, Kurds in Turkey were not

allowed to speak their own language in public or practice their customs.

About half of the world’s 25 million to 30 million Kurds live in Turkey. Six million to 7 million live in Iran, 3.5 million to 4 million live in Iraq, and 1.5 million live in Syria. Others are distributed in such countries as Armenia, Germany, Sweden, France, and the United States. Kurdish communities also exist in countries of the former Soviet Union.

The Kurds are an ancient people who trace their history back several thousand years. Like the Highland Scots, who have a clan history, Kurds have a tribal history. Kurds, like Scots, are often fiercely loyal to other members of their tribe. There are almost 800 separate tribes in Kurdistan. One can often identify the tribe from which a Kurd comes by his or her last name.

Even today, the isolation of the mountains has enabled local dynasties and tribes to flourish. In the absence of a central government, many Kurds considered their clan leaders to be their highest source of authority. At times, this has been an obstacle to Kurdish independence, as Kurds have been loyal to local leaders rather than to a Kurdish nation.

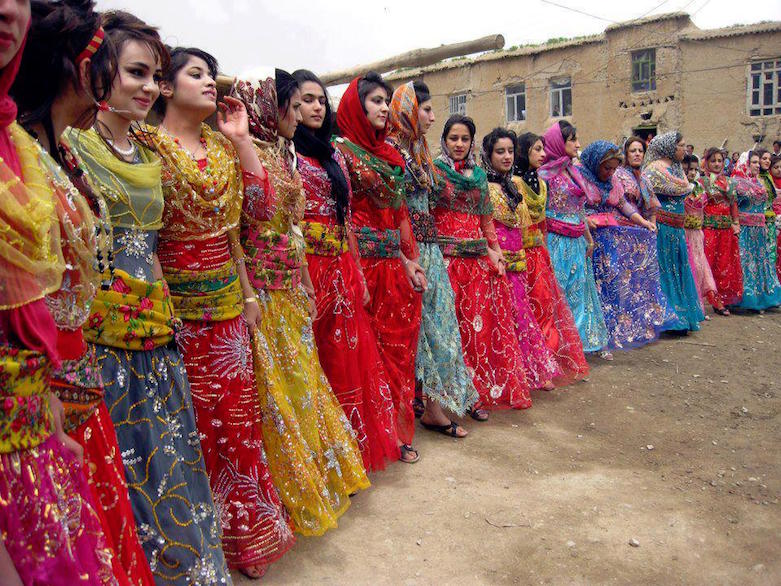

The Kurds are an Indo-European people with their own history, language, and culture. They are lovers of music, poetry, and dance. Most Kurdish villages and regions have their own dances. Men and women often dance together. Kurdish musicians play a type of flute (zornah) and drum (dohol). Kurds are fond of folk legends that tell of heroism, romance, and the love of country.

A love of flowers is reflected in the Kurdish native garb, which is as colorful as their mountain flowers in spring. Men wear fringed turbans, baggy pants, matching jackets, and cummerbunds tied around their waists, most in earth tones. Women wear long dresses of brightly colored fabric and coats often of brocade shot with silver or gold threads, baggy trousers, fancy vests, and headscarves. To see a Kurdish woman in her home setting is to see a riot of colors.

The mountains have shaped Kurdish history and culture. Kurds are great walkers and mountain climbers. They have learned to survive in the often-harsh conditions of the region. The winters are cold (with heavy snows for up to six months of the year), and earthquakes are not uncommon. Compared with most areas in the Middle East, which are dry, Kurdistan receives a considerable amount of precipitation.

The rain and snow run down the rugged mountainsides spilling onto the lowlands, filling the great Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Some of the grandest gorges in the world are in Kurdish country. Many people think that Gali Ali Beg in central Kurdistan is the grandest of them all.

The rain and snow run down the rugged mountainsides spilling onto the lowlands, filling the great Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Some of the grandest gorges in the world are in Kurdish country. Many people think that Gali Ali Beg in central Kurdistan is the grandest of them all.

Most of the major rivers of the Middle East run entirely or nearly entirely in Kurdistan. However, non-Kurds control the flow of most of these rivers. They regulate the waters for agricultural and industrial use and to generate electricity. The area is also known for its natural lakes and exceptionally powerful springs.

Because of the amount of rainfall, the soil of Kurdistan is rich. The mountainsides are covered with blankets of flowers. The flowers make a delicious meal for grazing sheep. In ancient times, Vikings traveled to Kurdistan to buy Kurdish butter because Kurdish sheep ate flowers as they foraged, and the butter had a delightful scent.

Kurds have long used the land for agricultural purposes, and some scholars believe Kurds invented farming. About 28 percent of the region is arable (suitable for farming), and many Kurds use the land to grow wheat and other cereals.

Higher in the mountains, the land is unfit for farming. Here herders pasture their sheep. Some lands, especially those on steep slopes and hard-to-reach plateaus, would not be used if not for these herders. Kurds use sheep and goats for their meat and their wool.

Water and fertile soil are not the only natural resources in Kurdistan. The region has some of the largest oil reserves in the Middle East and in the world. In ancient times, the Zagros and Taurus mountains were known as a great source for many metal ores, including copper, chromium, and iron. Though they are no longer considered a plentiful source of such minerals, the mountains are still mined.

Though today Kurdistan may seem isolated from the rest of the Middle East, at one time it was a center of civilization. It was located along the Silk Road – the trade route that linked Asia and Europe. Traders passing through would buy beautiful Kurdish rugs and other handicrafts. After the 1500s, however, traders began using sea routes and Kurdistan fell into a long period of decline. In this decade, Kurds are making themselves known once more.

-Saeedpour, Vera. “Meet the KURDS.” Faces: People, Places, and Cultures Mar. 1999

The following is an update to Dr. Saeedpour's article and brings together current (as of 2024) Kurdish issues and serves as a call to address these challenges through a balanced approach that promotes peace and respects Kurdish rights and autonomy.Current Issues Facing Kurdish Communities in 2024: A Complex Web of Conflict and Political Strife The Kurdish people, spread across Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran, have long sought greater autonomy and recognition. As one of the largest ethnic groups without a nation-state, the Kurds have encountered varied responses to their autonomy efforts, from support to outright military aggression. Today, Kurds face a host of challenges that are deeply interconnected with the political landscapes of these four countries and influenced by the strategic interests of global powers, particularly the United States and Turkey. The following sections outline some of the most pressing issues facing Kurdish communities in 2024.

Turkish Military Operations Against Kurdish Forces in Syria and Iraq In recent years, Turkey has ramped up military operations targeting Kurdish-controlled areas in northern Syria and Iraq. Turkish officials assert that these operations are necessary to neutralize groups like the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the People’s Protection Units (YPG). Ankara considers these groups as extensions of Kurdish militancy in Turkey, fearing they could inspire separatist movements within its borders. Despite the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) serving as a key U.S. partner in the fight against ISIS, Turkey remains staunchly opposed to Kurdish control in northern Syria. The Turkish government’s incursions have led to repeated airstrikes, displacing thousands of civilians and causing significant infrastructural damage. This dynamic places Syrian Kurdish communities in a precarious position, relying on the U.S. military presence to deter Turkish ground offensives while facing ongoing violence from cross-border drone strikes. The presence of U.S. troops in northeast Syria serves as a buffer against Turkish advances, but Kurdish leaders worry that an eventual U.S. withdrawal could embolden Turkish forces, intensifying the humanitarian crisis and threatening to destabilize the region further. As Kurdish officials have pointed out, should Turkey advance further into Kurdish-held territory, the SDF might be forced to divert its focus away from ISIS containment to defending its borders against Turkey—a development with serious implications for regional security.

Political Stalemate and Electoral Tensions in Iraqi Kurdistan In Iraqi Kurdistan, longstanding rivalries between the two dominant political factions—the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)—have led to a political deadlock. This has prevented the region from holding timely elections and risks undermining Kurdish self-governance. The dispute largely revolves around election reforms, specifically concerning reserved minority seats, which the PUK argues unfairly benefits the KDP. Efforts to conduct elections have been further complicated by intervention from the Iraqi Federal Supreme Court, which ruled that the Kurdistan Parliament’s previous extension of its term was unconstitutional. Consequently, the Iraqi electoral commission is now overseeing the elections, a move that some Kurdish leaders view as a challenge to Kurdish autonomy. For the first time, the KDP, historically a dominant player in Kurdish politics, finds itself unable to control the election’s outcome. This has prompted the KDP to boycott the process, potentially leading to further delays and eroding international confidence in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The deadlock is not only a blow to the region’s democratic aspirations but also opens the door to potential external interference. For instance, Baghdad, Tehran, and Ankara might attempt to leverage Kurdish divisions to weaken Kurdish autonomy and prevent any unified stance on Kurdish rights and self-determination in Iraq and beyond.

Fragile U.S.-Kurdish Alliance and the Threat of ISIS Resurgence The Kurdish-U.S. alliance, especially in Syria, has been instrumental in the campaign against ISIS, with Kurdish forces bearing much of the ground combat burden. However, the relationship is complex, shaped by competing U.S. commitments to NATO ally Turkey and to Kurdish-led forces. As ISIS regroups, particularly in detention facilities and remote areas, Kurdish forces continue to act as frontline defenders. However, Turkish threats of invasion raise serious concerns. Kurdish officials argue that Kurdish forces might have to redeploy from counter-ISIS operations to protect their borders from Turkish incursions, a move that could allow ISIS cells to rebuild and launch attacks.

In addition, Kurdish communities face worsening humanitarian conditions, with shortages in water and electricity compounding the region’s instability. Kurdish leaders have voiced fears that any disruption of the fragile U.S.-Kurdish cooperation could create a power vacuum, leaving communities vulnerable to both ISIS and Turkish aggression. This uncertainty has led to calls from Kurdish leaders to maintain a U.S. presence in the region until a political resolution can be achieved.

Renewed Hostilities in Turkey Following Ceasefire Collapse In Turkey, the PKK announced a temporary ceasefire following devastating earthquakes in early 2023, briefly de-escalating the violent conflict. However, this truce ended in mid-2023, and hostilities have since resumed, with Turkish forces undertaking numerous operations against PKK strongholds. The conflict, ongoing for decades, has claimed thousands of lives and continues to deepen ethnic tensions within Turkey. Military campaigns in southeastern Turkey and cross-border operations in Iraq aim to dismantle PKK infrastructure, but these efforts also contribute to civilian displacement and exacerbate animosity between Turkish and Kurdish populations. While the overall conflict’s intensity has decreased since its peak, the persistent lack of political resolution underscores the difficult path toward peace. Turkish efforts to curb Kurdish separatism continue to drive conflict, while Kurdish activists and politicians in Turkey remain subject to restrictive policies, which hinder Kurdish political expression and autonomy.

Conclusion The Kurdish people today find themselves at a crossroads. From political deadlock in Iraq to the threat of foreign invasion in Syria and Turkey, Kurds face a series of challenges that underscore the precarious nature of their autonomy and rights. The uncertain future of the U.S.-Kurdish alliance, combined with mounting pressure from Turkey and Iraq, leaves Kurdish communities in a vulnerable position, requiring both local resilience and international support to navigate a path toward stability. International actors must consider the impact of their actions on Kurdish communities and advocate for policies that ensure their security and rights. As Kurds continue to play a pivotal role in regional security, their stability and aspirations for self-determination are issues that demand the world’s attention.